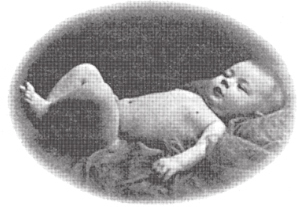

When I was four months old, my mother died suddenly and my father was left to look after me all by himself. This is how I looked at the time.

I had no brothers or sisters.

So all through my boyhood, from the age of four months onward, there was just us two, my father and me.

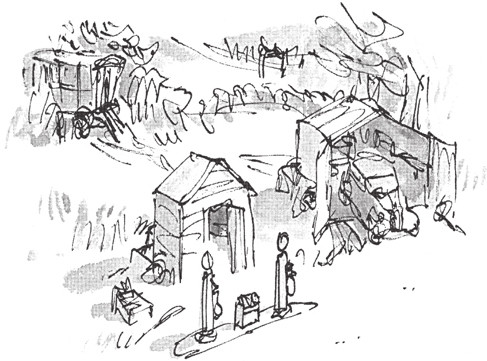

We lived in an old gypsy caravan behind a filling station. My father owned the filling station and the caravan and the small meadow behind, but that was all about he owned in the world, It was a very small filling station on a small country road surrounded by fields and woody hills.

While I was still a baby, my father washed me and fed me and changed my nappies and did all the millions of other things a mother normally does for her child. That is not an easy task for a man, especially when he has to earn his living at the same time by repairing motor car engines and serving customers with gasoline.

But my father didn’t seem to mind. I think that all the love he had felt for my mother when she was alive he now lavished upon me. During my early years, I never had a moment’s unhappiness or illness and here I am on my fifth birthday.

I was now a scruffy little boy as you can see, with grease and oil all over me, but that was because I spent all day in the workshop helping my father with the cars. The filling-station itself had only two pumps. There was a wooden shed behind the pumps that served as an office. There was nothing in the office except an old table and a cash register to put the money into. It was one of those where you pressed a button and a bell rang and the drawer shot out with a terrific bang. I used to love that.

The square brick building to the right of the office was the workshop. My father built that himself with loving care, and it was the only really solid thing in the place. “We are engineers, you and I,” he used to say to me. “We earn our living by repairing engines and we can’t do good work in a rotten workshop.” It was a fine workshop, big enough to take one car comfortably and leave plenty of room round the sides for working. It had a telephone so that customers could arrange to bring their cars in for repair.

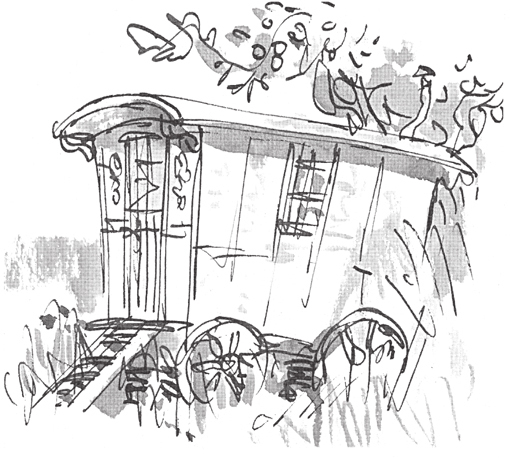

The caravan was our house and our home. It was a real old gipsy wagon with big wheels and fine patterns painted all over it in yellow and red and blue. My father said it was at least a hundred and fifty years old. Many gypsy children, he said, had been born in it and had grown up within its wooden walls. With a horse to pull it, the old caravan must have wandered for thousands of miles along the roads and lanes of England. But now its wanderings were over, and because the wooden spokes in the wheels were beginning to rot, my father had propped it up underneath with bricks.