"LADY?"

She looks up and out the window of the carriage; night has fallen with a swift and total blackness. She waits to see how she will be addressed.

For the first days of their journey, through the damp, twisting, dark-green trees of Breizh, she was Lady Roscille, the name pinned to her so long as she was in her homeland, all the way to the choky gray sea. They crossed safely, her father, Wrybeard, having beaten back the Northmen who once menaced the channel. The waves that brushed the ship's hull were small and tight, like rolled parchment.

Then, to the shores of Bretaigne—a barbarian little place, this craggy island which looks, on maps, like a rotted piece of meat with bites taken out of it. Their carriage gained a new driver, who speaks in bizarre Saxon. Her name, then, vaguely Saxon: Lady Rosele?

Bretaigne. First there had been trees, and then the trees had thinned to scruff and bramble, and the sky was sickishly vast, as gray as the sea, angry clouds scrawled across it like smoke from distant fires. Now the horses are having trouble with the incline of the road. She hears, but cannot see, rocks coming loose under their hooves. She hears the wind's long, smooth shushing, and that is how she knows it is only grass, grass and stone, no trees for the wind to get caught in, no branches or leaves to break the sound apart.

This is how she knows they have reached Glammis.

"Lady Roscilla?” her handmaiden prods her again, softly. There it is, the Skos. No, Scots. She will have to speak the language of her husband's people. Her people, now. “Yes?” Even under Hawise's veil, Roscille recognizes her quavering frown. “You haven't said a word in hours.”

“I have nothing to say.”

But that isn't entirely true; Roscille's silence is purposeful. The night makes it impossible to see anything out the window, but she can still listen, though she mostly hears the absence of sounds. No birds singing or insects trilling, no animals scuffling in the underbrush or scampering among the roots, no woodcutters felling oaks, no streams trickling over rock-beds, none of last night's rain dripping off leaves.

No sounds of life, and certainly no sounds of Breizh, which is all she has ever known. Hawise and her frown are the only familiar things here.

"The Duke will expect a letter from you when we arrive. When the proceedings are done,” Hawise says vaguely. Half a dozen names she has for the Lady, in as many tongues, but she has somehow not found the word for "wedding."

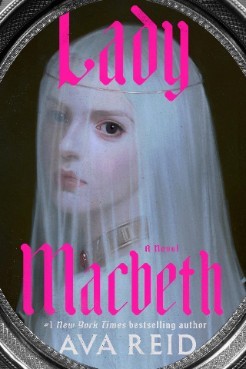

Roscille finds it funny that Hawise cannot speak the word when, at the moment, she is pretending to be a bride. Roscille thought it was a silly plan, when she first heard it, and it feels even sillier now: to disguise herself as handmaiden and Hawise as bride. Roscille is dressed in dull colors and stiff, blocky wool, her hair tucked under a coif. On the other side of the carriage, pearls circle Hawise's wrists and throat. Her sleeves are yawning mouths, drooping to the floor. The train is so white and thick it looks like a snowdrift has blown in. A veil, nearly opaque, covers Hawise's hair, which is the wrong shade of pale.