You ever seen a Klan march?

We don’t have them as grand in Macon, like you might see in Atlanta. But there’s Klans enough in this city of fifty-odd thousand to put on a food march when they get to feeling to.

This one on a Tuesday, the Fourth of July, which is today.

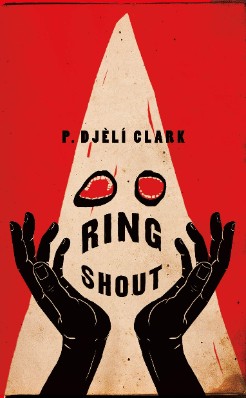

There’s a bunch parading down Third Street, wearing white robes and pointed hoods. Not a one got there face covered. I hear them first Klans after the Civil War hid behind the pillowcases and flour sacks to do their mischief, even blackened up to play like they colored. But this Klan we got in 1922 not concerned with hiding.

All of them—men, women, even little baby Klans—down there grinning like picnic on a Sunday. Got all kinds of fireworks—sparklers, Chinese crackers, sky rockets, and things that sound like cannons. A brass band competing with that racket, though everybody down there I swear clapping on the one and the three. With all the flag-waving and cavorting, you might forget they was monsters.

But I hunt monsters. And I know them when I see them.

“One little Ku Klux deaaaad,” a voice hums near my ears. “Two little Kluxes deaaaad, Three little Kluxes, Four little Kluxes, Five little Kluxes deaaaad.”

I glance to Sadie crouched beside me, hair pulled into a long brown braid dangling off a shoulder. She got one eye cocked, staring down the sights on her rifle at the crowd below as she finishes her ditty, pretending to pull the trigger.

Click, click, click, click, click!

“Stop that now.” I push away the rifle barrel with a beaten-up book. “That thing go off and you liable to make me deaf. Besides, somebody might catch sight of us.”

Sadie rolls big brown eyes at me, twisting her lips and lobbing a spitty mess of tobacco onto the rooftop. I grimace. Girl got some disgusting habits.

“I swear Maryse Boudreaux.” She slings her rifle across blue overalls too big for her skinny self and puts hands to her hips to give me the full Sadie treatment, looking like some irate yella gal sharecropper. “The way you always worrying. Is you twenty-five or eighty-five? Sometimes I forget. Ain’t nobody seeing us way up here but birds.”

She gestures out at buildings rising higher than the telegraph lines of downtown Macon. We up on one of the old cotton warehouses off Poplar Street. Way back, this whole area housed cotton coming in from countryside plantations to send down the Ocmulgee by steamboat. That fluffy white soaked in slave sweat and blood what made this city. Nowadays Macon warehouses still hold cotton, but for local factory mills and railroads. Watching these Klans shamble down the street, I’m reminded of bales of white, still soaked in colored folk sweat and blood, moving for the river.

“Not too sure about that,” Chef puts in. She sits with her back against the rooftop wall, dark lips curled around the butt of a Chesterfield in a familiar easy smirk. “Back in the war, we always watched for snipers. ‘Keep one eye on the mud, one in the front, and both up on top,’ Sergeant used to say. Somebody yell, ‘Sniper!’ and we scampered quick!” Beneath a narrow mustard-brown army cap her eyes tighten and the smirk wavers. She pulls out the cigarette, exhaling a white stream. “Hated fucking snipers.”