It was dawn, and the zombies were stumbling through the parking lot, streaming toward the massive beige box at the far end. Later they’d be resurrected by megadoses of Starbucks, but for now they were the barely living dead. Their causes of death differed: hangovers, nightmares, strung out from epic online gaming sessions, circadian rhythms broken by late-night TV, children who couldn’t stop crying, neighbors partying till 4 a.m., broken hearts, unpaid bills, roads not taken, sick dogs, deployed daughters, ailing parents, midnight ice cream binges.

But every morning, five days a week (seven during the holidays), they dragged themselves here, to the one thing in their lives that never changed, the one thing they could count on come rain, or shine, or dead pets, or divorce: work.

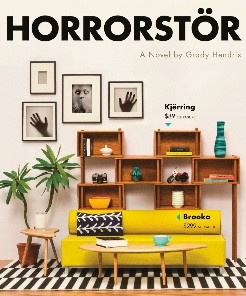

Orsk was the all-American furniture superstore in Scandinavian drag, offering well-designed lifestyles at below-Ikea prices, and its forward-thinking slogan promised “a better life for the everyone.” Especially for Orsk shareholders, who trekked to company headquarters in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, every year to hear how their chain of Ikea knockoff stores was earning big returns. Orsk promised customers “the everything they needed” in the every phase of their lives, from Balsak cradles to Gutevol rocking chairs. The only thing it didn’t offer was coffins. Yet.

Orsk was an enormous heart pumping 318 partners—228 full-time, 90 part-time—through its ventricles in a ceaseless circular flow. Every morning, floor partners poured in to swipe their IDs, power up their computers, and help customers size the perfect Knäbble cabinets, find the most comfortable Müskk beds, and source exactly the right Lågniå water glasses. Every afternoon, replenishment partners flowed in and restocked the Self-Service Warehouse, pulled the picks, refilled the impulse bins, and hauled pallets onto the Market Floor. It was a perfect system, precision-engineered to offer optimal retail functionality in all 112 Orsk locations across North America and in its thirty-eight locations around the world.

But on the first Thursday of June at 7:30 a.m., at Orsk Location #00108 in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, this well-calibrated system came grinding to a halt.

The trouble started when the card reader next to the employee entrance gave up the ghost. Store partners arrived and piled up against the door in a confused chaotic crowd, helplessly waving their IDs over the scanner until Basil, the deputy store manager, appeared and directed them all to go around the side of the building to the customer entrance.

Customers entered Orsk through a towering two-story glass atrium and ascended an escalator to the second floor, where they began a walk of the labyrinthine Showroom floor designed to expose them to the Orsk lifestyle in the optimal manner, as determined by an army of interior designers, architects, and retail consultants. Only here was yet another problem: the escalator was running down instead of up. Floor partners shoved their way into the atrium and came to a baffled halt, unsure what to do next. IT partners jammed up behind them, followed by a swarm of postsales partners, HR partners, and cart partners. Soon they were all packed in butt to gut and spilling out the double doors.

Amy spotted the human traffic jam from across the parking lot as she power-walked toward the crowd, a soggy cup of coffee leaking in one hand.

“Not now,” she thought. “Not today.”

She’d bought the coffee cup at the Speedway three weeks ago because it promised unlimited free refills and Amy needed to stretch her $1.49 as far as it would go. This was as far as it went. As she stared in dismay at the mass of partners, the bottom of her cup finally gave up and let go, dumping coffee all over her sneakers. Amy didn’t even notice. She knew that a crowd meant a problem, and a problem meant a manager, and this early in the day a manager meant Basil. She could not let Basil see her. Today she had to be Basil Invisible.