I must have been very young when I saw the mermaids at the Cirque de la Mer because it was my nurse who took me, and her place in my life was soon surrendered to tutors. I don’t think my father ever found out. He would not have approved.

The day is little more than a sensory haze of pastel children, the laughter of strangers, and the burn of salt and chemicals at the back of my throat. The mermaids, though. They are as vivid as stained glass, even now.

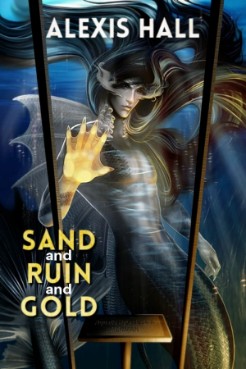

There were three I saw perform—Neaera, Arethusa, Ianessa—though it was for Neaera that the crowd went wild. She was the number one attraction, her image on every poster, shining, beautiful, and perfectly iconic: copper skin, burnished golden scales, the untamed waves of her dark-green hair. I didn’t know, then, that she was the cirque’s seventh Neaera.

It is that particular combination of hair and skin and scales, at least according to market research, that best meets our ideal image of a mermaid.

And it’s right.

She was sun and sky and flame that day.

And I thought I had never seen anything so beautiful, or so free.

I was young.

I didn’t know any better.

When I turned eighteen, I ran away from home to join the cirque.

I had tried at fourteen, and sixteen, but they always brought me back. I never told anyone where I was going or why. I never told them about the mermaids.

My father was bewildered. He had hired the best geneticians in the country to create me. I was supposed to be flawless, and when he returned me to the lab, once, twice, three times, they assured him I was.

I was. I am.

Everything he coded into me is there. Everything that should have made me just like him.

But something got into my heart that day at the cirque. A piece of grit, love, or beauty, or hope. Words we didn’t use so much anymore.

I thought you would need special knowledge or advanced training, perhaps some kind of background in marine biology, to be allowed to work with the Mer. But, no, all you need is the desire and—I would learn later— the ability to look good in a wetsuit, and I possessed all those things. My father was vain enough to make me an ideal in ways beyond the merely intellectual.

I didn’t know if the years had changed the Cirque de la Mer, or if they had changed me, but it was strange at first to see beyond the veil of enchantment to dingy pools and peeling paint, grey concrete beneath a grey sky, in the empty times after closing when there was no laughter left. But, in some ways, that was when I liked it best, when it was ours again—we who waited when everyone else went home.

You have to understand, we did it all for love. We offered these glimpses of glorious things, too dazzled ourselves to see the truth of what we did. And the crowds flocked.

I worked without particular affiliation at first, going wherever I was needed, doing whatever I was told—scrubbing buckets, cleaning tanks and filters, injecting the necessary vitamins and antibiotics into the frozen fish that were delivered daily in huge crates. But whenever I could, I watched the mermaids, learned their names, their ways.