Every seance I conducted with Mama followed a pattern.

In the small room at the front of the house, we—the clients, Mama, and I—would sit with linked hands around a table covered in dark velvet. The only light would come from the cheap candles she had lit before. They were crumbly, and the wicks often spluttered, throwing fantastic shadows on the wallpaper. As the candles burning, the wax tended to run dreadfully, staining the sideboards as it congealed. It was for this reason that she kept buying them. She said it created the right sort of ambience.

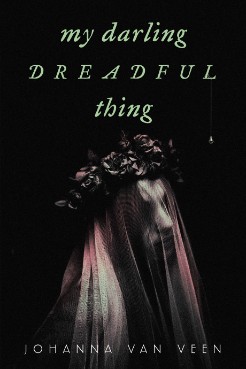

Poor Mama truly went to a great deal of trouble to spin her illusions. Not only did she invest in that black velvet tablecloth and the candles that would gutter out unexpectedly, she had also bought a crystal ball and large age-speckled mirrors that she would drape with gauze, giving the impression of a house in mourning. The way I addressed her, too, was part of the elaborate fantasy she spun. I called her Mama because she demanded it be so; it made us sound genteel, which gave her an air of respectability and made it seem as if she organized these seances not from a need for money but to help the bereaved.

"These communications are a terrible strain on my darling daughter," she'd tell the new clients, though she preferred to call them our guests because, although she desired money, she thought it vulgar to speak of it. "Frankly, there are times when her little talent seems more like a curse than a blessing. The war left so many dead, didn't it? And in such gruesome ways, too. Starvation and bombs and gas chambers... But she's so eager to help, the dear girl. 'I must help these poor souls, Mama, and it doesn't matter how much it hurts.' She's such a selfless thing, you see.

Then she'd take a handkerchief hemmed with frothy lace from her pocket and dab at her dry eyes, her silver bangles clinking around her wrists. The shivering sound they produced when they clanked together could hide a multitude of sins. She wore black dresses of thick stiff materials that rustled as she moved. Her hair, she piled on top of her head in complicated heaps.

I, on the other hand, wore my hair loose. Mama brushed it before every session so it looked neat and shiny. I wore white summer dresses that were invariable too thin for the weather. Those dresses hung around my frame, making me look small and thin, a proper waif dressed in a child's nightgown. This, too, and intentional: she wanted me to look like a little girl, innocent and defenseless. When I got into one of my trances and thrashed and moved about, the dress would slip down my shoulders and reveal the satin slip I wore underneath, and some of our male guests would suppress a moan.

Mama presented me as a child, yes, but one ripe and ready.

"Nothing," she told me, "appeals more to a man than a young girl who's not been had yet, apart from a girl who's not been had yet and gives the impression she'll be had by him." She made me think of myself as a piece of fruit and the act of sex like plucking a plum with a rough hand, bruising the flesh.