Tomás decides to walk.

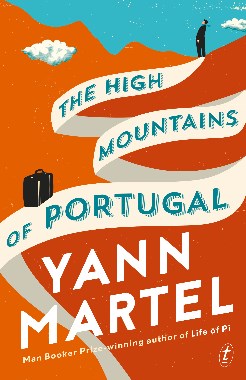

From his modest flat on Rua São Miguel in the ill-framed Alfama district to his uncle’s stately estate in leafy Lapa, it is a good walk across much of Lisbon. It will likely take him an hour. But the morning has broken bright and mild, and the walk will soothe him. And yesterday Sabio, one of his uncle’s servants, came to fetch his suitcase and the wooden trunk that holds the documents he needs for his mission to the High Mountains of Portugal, so he has only himself to convey.

He feels the breast pocket of his jacket. Father Ulisses’ diary is there, wrapped in a soft cloth. Foolish of him to bring it along like this, so casually. It would be a catastrophe if it were lost. If he had any sense he would have left it in the trunk. But he needs extra moral support this morning, as he does every time he visits his uncle.

Even in his excitement he remembers to forgo his regular cane and take the one his uncle gave him. The handle of this cane is made of elephant ivory and the shaft of African mahogany, but it is unusual mainly because of the round pocket mirror that juts out of its side just beneath the handle. This mirror is slightly convex, so the image it reflects is quite wide. Even so, it is entirely useless, a failed idea, because a walking cane in use is by its nature in constant motion, and the image the mirror reflects is therefore too shaky and fleeting to be helpful in any way. But this fancy cane is a custom-made gift from his uncle, and every time he pays a call Tomás brings it.

He heads off down Rua São Miguel onto Largo São Miguel and then Rua de São João da Praça before turning onto Arco de Jesus – the easy perambulation of a pedestrian walking through a city he has known his whole life, a city of beauty and bustle, of commerce and culture, of challenges and rewards. On Arco de Jesus he is ambushed by a memory of Dora, smiling and reaching out to touch him. For that, the cane is useful, because memories of her always throw him off balance.

“I got me a rich one,” she said to him once, as they lay in bed in his flat.

“I’m afraid not,” he replied. “It’s my uncle who’s rich. I’m the poor son of his poor brother. Papa has been as unsuccessful in business as my uncle Martim has been successful, in exact inverse proportion.”

He had never said that to anyone, commented so flatly and truthfully about his father’s checkered career, the business plans that collapsed one after the other, leaving him further beholden to the brother who rescued him each time. But to Dora he could reveal such things.

“Oh, you say that, but rich people always have troves of money hidden away.”

He laughed. “Do they? I’ve never thought of my uncle as a man who was secretive about his wealth. And if that’s so, if I’m rich, why won’t you marry me?”

People stare at him as he walks. Some make a comment, a few in jest but most with helpful intent. “Be careful, you might trip!” calls a concerned woman. He is used to this public attention; beyond a smiling nod to those who mean well, he ignores it.

One step at a time he makes his way to Lapa, his stride free and easy, each foot lifted high, then dropped with aplomb. It is a graceful gait.